Anywhere you go in France or in the world, for any event be it a football match, a presidential election or a music concert, there will be a Breton flag. This is Brittany’s soft power and cultural expression. Although it is a pretty small region of France, Brittany’s history and cultural identity is powerful.

Brittany, located in North-Western France, initially joined the Kingdom of France in 1532 as an independent entity and was integrated into France following the French Revolution.

Today, Brittany is mostly known for its cultural traditions, food and touristic places like Saint Malo or Brest. However, it has also been used by political parties to promote autonomy claims. According to polls, carried by the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in 2008, 22.5% of the Breton people interviewed feel more Breton than French. In this article, we examine how these claims materialize and could disrupt the French unified system of regions.

The Gwenn Ha Du and independence movements Breton flag

Breton flag

At the beginning of the 20th century there was a revival of the Breton culture. This movement fabricated and popularized a homogeneous Breton culture – using elements like the dancing events Festoù Noz, or the instrument Biniou, but also the Celtic tradition and folklore. It was also at this time that Bretons began developing a common dictionary of ‘Breton language’. Meanwhile, some nationalists used this cultural revival to make political claims, with the creation of the ‘Groupe Régionaliste Breton’ by Morvan Marchal and Henri Prado. They created the popular black and white flag called the Gwenn Ha Du. The political movement justified its existence on the claim that Republican France was destroying Breton culture and Breton identity. In 1940, when the Germans invaded France, the Breton independentists seized the opportunity to weaken French institutions in Brittany and cooperated with the Gestapo. Some carried out executions in small Breton villages against people who were ‘too Francophile’. In the words of Morvan Marchal: “The same preoccupation holds for nationalism of small countries: get the intelligence of its people back from the foreign culture imposed on them and reconstruct a national civilisation on racial and traditional basis”. Autonomists or independentist movements in Brittany shared a common preoccupation: France is destroying Breton culture. At the end of the War, the movement was obliterated, and since then, only few radical movements have argued for total independence from France. As explained in the introduction, a significant amount of people in Brittany still feel more Breton than French, but today they embrace the culture without rebelling against French institutions. Translation: “Because he spoke Breton”

Translation: “Because he spoke Breton”

The Breton Language

Today, the political parties that claim a Breton identity use language as their most defining feature. The ‘Breton language’ is spoken by 5 % of the population in Brittany and is close to extinction. This is because of the French reforms carried out in 1881 that forbade its use in primary school. The ‘Education Nationale’ has always tried to marginalize all other languages than French to avoid any competition with the language of the nation. However, a segment of the population is still fighting for the revival, or rather survival of this language. More than 90 schools called ‘Diwan’ are Breton-speaking and teach only in Breton language. We interviewed, Joëlle Perrot, a teacher from one of these schools about their cultural project. For her, the Diwan schools are trying to “preserve a heritage that is disappearing”. Concerning the Education Nationale [Ministry of National Education] she comments: “It is a shame that there is no room for diverse languages and cultures of France other than French”. The ‘Breton language’ is central to the identity of Bretons and Diwan schools; rather than threatening the hegemony of French, it fights more for cultural recognition than nationalism. On this subject, she adds that “the learning of regional languages and culture in school programs would not have affected the unity of the nation, it would only have made it richer, more open and more tolerant.” Therefore, in Breton identity and cultural movement, it is this fact that remains: the overwhelming French nationalism is destroying other regional identities, even though they would not be threatening to its authority.

Political claims Parti Breton logo

Parti Breton logo

Despite the mostly culturally grounded identity of Brittany, politics are also involved in promoting this cultural identity. Several political parties have competed in elections using autonomy claims in recent years; among them the Breton Party (PB), the “Yes Brittany” (Oui la Bretagne) and the Breizhistance party are the most influential. They all advocate for a greater Brittany, recognised as autonomous and as bearing a Breton identity that needs not be undermined by the French central government. Hence, coming back to our previous point, language for instance is specifically targeted by autonomist parties as a unifying common feature. For instance, the PB advocates for the institutionalisation of bilingualism as a norm in Brittany where schools, hospitals and administrations would work in both French and Breton. This cultural normativity links identity and politics as language is used as a tool to legitimize the existence of Brittany as a sole bearer of a cultural specificity that has been denied and oppressed by the French system for decades.

Autonomy aspirations grounded in European inspirations

The PB goes further and claims that “Brittany must recover its rights as a nation within the European Union”. Breton independence parties are particularly inspired by the autonomous movements lead by other parties in France like in Corsica and in Europe such as the Scottish National Party. The Breton Party envisions the creation of political institutions such as a Parliament to defend the unalienable historical rights of Brittany to add to the already existing Breton Press Agency (Agence Bretagne Presse). The party also denounces the oppression imposed by the centralized French system on the region and it supports the reassertion of local authority through a “real” local and participatory democracy. Although such parties campaign for the political identity of Brittany, they do not deny the existence of other identities, they advocate for more independence in terms of schooling and economic development. Independence movements in Europe

Independence movements in Europe

As opposed to other movements in Europe like the Catalonian one, the Breton movement for autonomy is grounded mostly in a bid for cultural reassertion rather than concrete political independence. Furthermore, the party lacks the support other European parties benefit from.

Yielding votes in a highly centralized system

Several constraints have prevented these parties from making a considerable move into Breton politics. Firstly, the French centralized state is very powerful and national parties yield more votes and benefit from more visibility than local/regional parties. Secondly, even within Brittany, the political parties are numerous and various and defend different goals, so no alliance is erected. Therefore, votes are not collected unanimously which hinders their outbreak into politics, vote yields testifying for the lack of political support in the region. For instance, in the 2015 regional elections, although Christian Troadec, leader of the Oui la Bretagne party managed to be the fourth party in Brittany, it only gained 6.7% of the votes. Ultimately, many Bretons support their region and the cultural identity associated with it, however, the French centralized political system remains reliable enough for them to identify to it.

Conclusion:

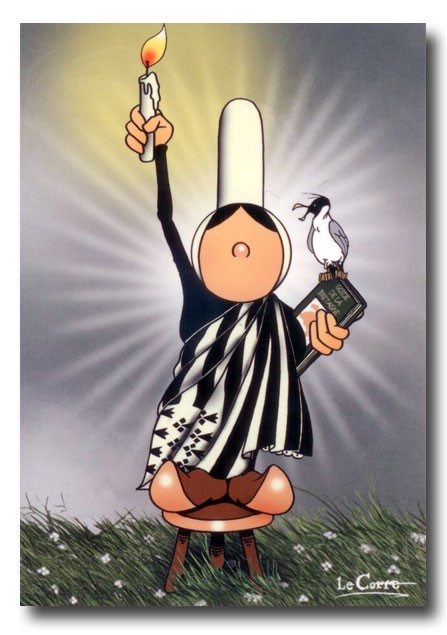

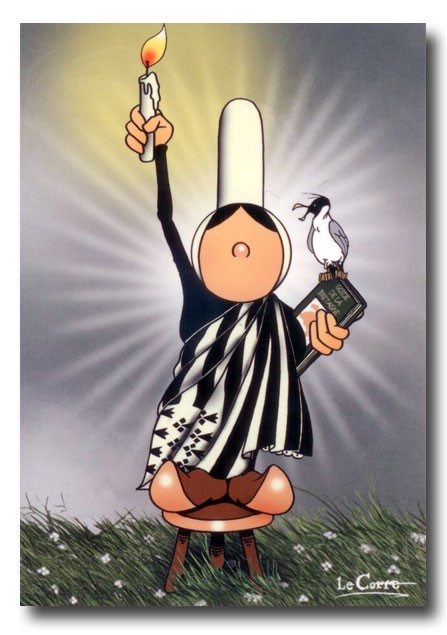

Breton identity is undeniably culturally powerful and influential within and outside its borders. In the past, Breton culture has been used by groups to gain political authority over Brittany and independence from French institutions. Today, claims for more autonomy are grounded in the specifics of the Breton language and are a reaction to the homogenising processes of French nationalism. However, political movements which defend a more autonomous status for the region have failed to yield much support from the population. Traditional costume of Brittany disguised in the Statue of Liberty

Traditional costume of Brittany disguised in the Statue of Liberty

Bevet Breizh!

As native Breton students, Justine and Anne both study International Relations at King’s College London. Justine is interested in Indian nation-building and climate change related issues. Anne is interested in Lebanese politics and foreign policy crisis resolution.

Source

Brittany, located in North-Western France, initially joined the Kingdom of France in 1532 as an independent entity and was integrated into France following the French Revolution.

Today, Brittany is mostly known for its cultural traditions, food and touristic places like Saint Malo or Brest. However, it has also been used by political parties to promote autonomy claims. According to polls, carried by the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) in 2008, 22.5% of the Breton people interviewed feel more Breton than French. In this article, we examine how these claims materialize and could disrupt the French unified system of regions.

The Gwenn Ha Du and independence movements

Breton flag

Breton flag At the beginning of the 20th century there was a revival of the Breton culture. This movement fabricated and popularized a homogeneous Breton culture – using elements like the dancing events Festoù Noz, or the instrument Biniou, but also the Celtic tradition and folklore. It was also at this time that Bretons began developing a common dictionary of ‘Breton language’. Meanwhile, some nationalists used this cultural revival to make political claims, with the creation of the ‘Groupe Régionaliste Breton’ by Morvan Marchal and Henri Prado. They created the popular black and white flag called the Gwenn Ha Du. The political movement justified its existence on the claim that Republican France was destroying Breton culture and Breton identity. In 1940, when the Germans invaded France, the Breton independentists seized the opportunity to weaken French institutions in Brittany and cooperated with the Gestapo. Some carried out executions in small Breton villages against people who were ‘too Francophile’. In the words of Morvan Marchal: “The same preoccupation holds for nationalism of small countries: get the intelligence of its people back from the foreign culture imposed on them and reconstruct a national civilisation on racial and traditional basis”. Autonomists or independentist movements in Brittany shared a common preoccupation: France is destroying Breton culture. At the end of the War, the movement was obliterated, and since then, only few radical movements have argued for total independence from France. As explained in the introduction, a significant amount of people in Brittany still feel more Breton than French, but today they embrace the culture without rebelling against French institutions.

Translation: “Because he spoke Breton”

Translation: “Because he spoke Breton” The Breton Language

Today, the political parties that claim a Breton identity use language as their most defining feature. The ‘Breton language’ is spoken by 5 % of the population in Brittany and is close to extinction. This is because of the French reforms carried out in 1881 that forbade its use in primary school. The ‘Education Nationale’ has always tried to marginalize all other languages than French to avoid any competition with the language of the nation. However, a segment of the population is still fighting for the revival, or rather survival of this language. More than 90 schools called ‘Diwan’ are Breton-speaking and teach only in Breton language. We interviewed, Joëlle Perrot, a teacher from one of these schools about their cultural project. For her, the Diwan schools are trying to “preserve a heritage that is disappearing”. Concerning the Education Nationale [Ministry of National Education] she comments: “It is a shame that there is no room for diverse languages and cultures of France other than French”. The ‘Breton language’ is central to the identity of Bretons and Diwan schools; rather than threatening the hegemony of French, it fights more for cultural recognition than nationalism. On this subject, she adds that “the learning of regional languages and culture in school programs would not have affected the unity of the nation, it would only have made it richer, more open and more tolerant.” Therefore, in Breton identity and cultural movement, it is this fact that remains: the overwhelming French nationalism is destroying other regional identities, even though they would not be threatening to its authority.

Political claims

Parti Breton logo

Parti Breton logo Despite the mostly culturally grounded identity of Brittany, politics are also involved in promoting this cultural identity. Several political parties have competed in elections using autonomy claims in recent years; among them the Breton Party (PB), the “Yes Brittany” (Oui la Bretagne) and the Breizhistance party are the most influential. They all advocate for a greater Brittany, recognised as autonomous and as bearing a Breton identity that needs not be undermined by the French central government. Hence, coming back to our previous point, language for instance is specifically targeted by autonomist parties as a unifying common feature. For instance, the PB advocates for the institutionalisation of bilingualism as a norm in Brittany where schools, hospitals and administrations would work in both French and Breton. This cultural normativity links identity and politics as language is used as a tool to legitimize the existence of Brittany as a sole bearer of a cultural specificity that has been denied and oppressed by the French system for decades.

Autonomy aspirations grounded in European inspirations

The PB goes further and claims that “Brittany must recover its rights as a nation within the European Union”. Breton independence parties are particularly inspired by the autonomous movements lead by other parties in France like in Corsica and in Europe such as the Scottish National Party. The Breton Party envisions the creation of political institutions such as a Parliament to defend the unalienable historical rights of Brittany to add to the already existing Breton Press Agency (Agence Bretagne Presse). The party also denounces the oppression imposed by the centralized French system on the region and it supports the reassertion of local authority through a “real” local and participatory democracy. Although such parties campaign for the political identity of Brittany, they do not deny the existence of other identities, they advocate for more independence in terms of schooling and economic development.

Independence movements in Europe

Independence movements in Europe As opposed to other movements in Europe like the Catalonian one, the Breton movement for autonomy is grounded mostly in a bid for cultural reassertion rather than concrete political independence. Furthermore, the party lacks the support other European parties benefit from.

Yielding votes in a highly centralized system

Several constraints have prevented these parties from making a considerable move into Breton politics. Firstly, the French centralized state is very powerful and national parties yield more votes and benefit from more visibility than local/regional parties. Secondly, even within Brittany, the political parties are numerous and various and defend different goals, so no alliance is erected. Therefore, votes are not collected unanimously which hinders their outbreak into politics, vote yields testifying for the lack of political support in the region. For instance, in the 2015 regional elections, although Christian Troadec, leader of the Oui la Bretagne party managed to be the fourth party in Brittany, it only gained 6.7% of the votes. Ultimately, many Bretons support their region and the cultural identity associated with it, however, the French centralized political system remains reliable enough for them to identify to it.

Conclusion:

Breton identity is undeniably culturally powerful and influential within and outside its borders. In the past, Breton culture has been used by groups to gain political authority over Brittany and independence from French institutions. Today, claims for more autonomy are grounded in the specifics of the Breton language and are a reaction to the homogenising processes of French nationalism. However, political movements which defend a more autonomous status for the region have failed to yield much support from the population.

Traditional costume of Brittany disguised in the Statue of Liberty

Traditional costume of Brittany disguised in the Statue of Liberty Bevet Breizh!

As native Breton students, Justine and Anne both study International Relations at King’s College London. Justine is interested in Indian nation-building and climate change related issues. Anne is interested in Lebanese politics and foreign policy crisis resolution.

Source