On 8 April 2021, the French National Assembly has witnessed a small revolution with the adoption, against the government’s opinion, of a law aimed to protect and promote regional languages. This law was drafted and supported by Paul Molac, Member of the Parliament from the Regions and Peoples with Solidarity party from the constituency of Ploërmel, Brittany. This adoption undermines the French State’s Jacobinism.

Since the Deixonne Law [first French law authorising the teaching of French regional languages] in 1951, no law was ever adopted on the issue of so-called “regional” languages. The latter have been enshrined in the French Constitution, but in article 75-1 rather than 2, meaning they are not official languages of the Republic.

Let’s make things clear right away: this law will not “save the Breton language”, nor any other minority language. Saving a language is speaking it, first and foremost! We are also still far from equality between languages and cultures. However, in managing to get this law adopted after a first unsuccessful attempt in 2015, Paul Molac has rid activists and politicians from various worries.

The question of diacritical signs, for instance (the ñ in Fañch especially) should be solved once and for all. In addition, if a town does not offer bilingual teaching, an obligation for them to pay a forfait scolaire [fee paid by the town to support other schools that do offer this option] was just voted. This is an important financial security for Diwan (Breton), Ikastola (Basque) or Calendreta (Occitan) school networks. Even better, public education will now be able to go beyond hourly parity [between French and a regional language] and toward immersion. This is the part of the text that has triggered the most debates, since some Members of the Parliament believe immersion to be a threat to the “mastering of French”!

Minister of National Education Jean-Michel Blanquer has really shown bad faith during this debate, stressing he was “not against regional languages” but refusing to acknowledge and support the best pedagogical method to learn them. Can one say they are favorable to a language if one doesn’t wish for it to be alive? Let’s remember that Breton is not transmitted by families (or very little) and that without school (and long-term training for adults), it dies.

“Few understand the [French] government’s obsession for maintaining a hierarchy between languages”

This small victory is perhaps the expression of a more profound ideological shift in French society. Today, few understand the government’s obsession for maintaining a hierarchy between languages. The most evident discriminations toward minority languages are deemed unfair and the more the State mistreats these languages, the more support they gain within the population.

This debate has shown how fragile the French Republic is, in Jacobins’ minds. Should close to 70 million French speakers in France feel threatened by a network of schools like Diwan, counting around… 4,000 pupils?

Diwan, in Breton, means “seed”. Yet one knows how much language is a pilar of French identity. Sharing space with the French language, making other languages spoken in France co-official (we are far from it), would mean accepting the idea that the French are not the only ones living in France. Recognising there is a difference between citizenship and nationality. In other words, a certain idea of cultural diversity! It’s on its way…

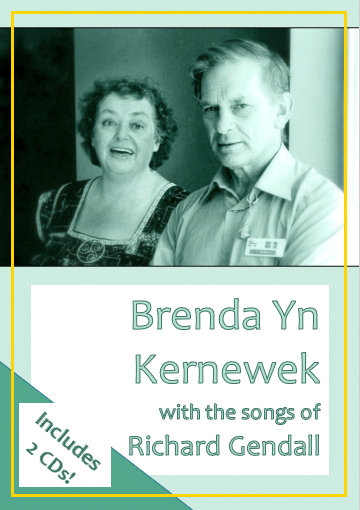

ecordings

of songs in Cornish performed by Brenda - some are taken from her LPs,

but there are several that are unpublished: concert recordings, practice

tapes etc. In addition, we have the 2 unused songs of Richard's

recorded by our Guest Artists, Hilary Coleman and Neil Davey, and

Gwenno, bringing the total to 33. There is an extensive introduction

with biographical information about Brenda and Richard, with the focus

on the reclusive Richard Gendall, about whom much less is known, and

insights into his motivations. I have added a table in the Appendix with

the complete list of Richard's Cornish songs of which I have some

evidence - lyrics, music and/or recordings, if there should be further

interest.

ecordings

of songs in Cornish performed by Brenda - some are taken from her LPs,

but there are several that are unpublished: concert recordings, practice

tapes etc. In addition, we have the 2 unused songs of Richard's

recorded by our Guest Artists, Hilary Coleman and Neil Davey, and

Gwenno, bringing the total to 33. There is an extensive introduction

with biographical information about Brenda and Richard, with the focus

on the reclusive Richard Gendall, about whom much less is known, and

insights into his motivations. I have added a table in the Appendix with

the complete list of Richard's Cornish songs of which I have some

evidence - lyrics, music and/or recordings, if there should be further

interest.